By: Daniel Reyes, co-founder of CTMS and founder of Myco Alliance

Join us online for a class with Daniel about Applied Mycology.

Back in 2013, while working as a hydrogeologist in the oil and gas industry, I reached out to my friend Mike Wolfert for advice on mushroom cultivation. Little did I know, this simple conversation would spark a massive change in the course of my career. Mike Wolfert, known for his work in regenerative agriculture and permaculture through organizations like Symbiosis TX (formerly One World Permaculture), became a key figure in my journey. Over the course of several months, I kept looking for opportunities to learn all I could about mycology while I kept my career job.

I did a lot of self learning until I heard about these guys out by Dripping Springs who were growing edible mushrooms. I started volunteering on the weekends at LoGro Farms, where I marveled at their innovative approach to sustainability. There, the circular economy was alive and thriving: Jester King Brewery sent their spent beer rains to LoGro, where they were repurposed as substrate for mushroom cultivation. LoGro then produced mushrooms from this waste, which became a key ingredient in tanley's pizza and a staple in Jester King's famous Snorkel mushroom beer. This closed-loop system not only minimized waste but also maximized resource efficiency, inspiring me to rethink waste management in the mushroom farming industry.

While volunteering at LoGro Farms, where sustainability thrived as a core principle, I stumbled upon a notable hurdle: spent mycelium blocks, cast aside after only a handful of harvests. As I observed the stacks of discarded mycelium blocks from the production of their mushroom kits, it became clear that there was more to their story than mere waste. These blocks, once bursting with life as a vital component of mushroom cultivation, now languished in neglect, awaiting their fate in the discard pile. Yet, amidst their apparent insignificance, I saw a hidden opportunity—an opportunity to breathe new life into these discarded remnants.

I went back to Mike and suggested we could put these discarded blocks to good use in a project. I explained how these blocks, instead of being thrown away, could be used to strengthen swales and berms. Mike was intrigued. We brainstormed ways to make it happen, considering how these blocks could improve soil health and help plants grow. By incorporating spent mycelium blocks into swales and berms, we aimed to enhance their functionality and ecological benefits. The mycelium, with its intricate network of hyphae, acts as a natural binder, strengthening soil structure and promoting water etention. As these blocks break down over time, they contribute organic matter and nutrients to the surrounding soil, enriching its fertility and supporting plant growth.

In pursuit of expanding my knowledge and impact in the realm of applied mycology and environmental remediation, I journeyed to the Ecuadorian Amazon basin later that year into the Sucumbios region. Drawing from my background in hydrogeology and having been recently inoculated with the ethos of circularity nurtured at LoGro Farms and guided by Mike's wisdom in permaculture practices, I endeavored to seamlessly intertwine these ideologies in the Ecuadorian context.

Navigating the complexities of Amazonian ecosystems and addressing environmental challenges. We initiated projects to strengthen resilience and promote sustainable living practices. One of the key challenges we faced was sourcing suitable spawn for our projects. While commercial strains were readily available in the capital city of Quito, they were ill-suited for the unique conditions of the Amazon. We recognized the importance of using native strains, tolerant to the region's environment, to ensure the success of our initiatives and for that reason began to work only with producers of native, resilient strains.

Against the backdrop of environmental degradation and industrial impact, we were acutely aware of the region's history, including the devastating legacy of Texaco's oil drilling operations in the Lago Agrio oil field. Texaco's irresponsible waste disposal practices in the 1960’s, amounting to billions of gallons of oil dumped into unlined pits, had left a lasting scar on the ecosystem, poisoning water supplies and threatening indigenous livelihoods.

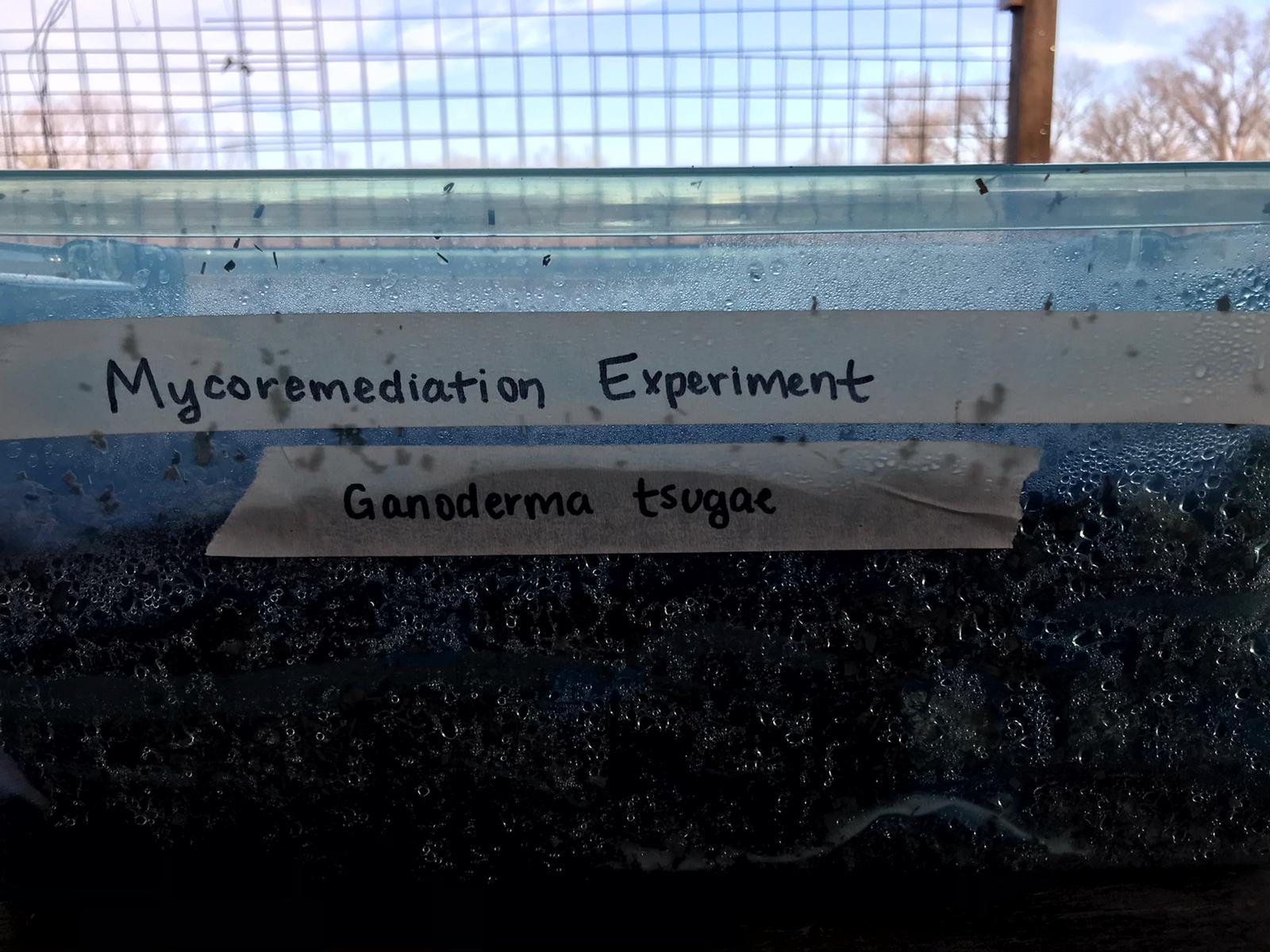

In 2015, following my return from Ecuador, I initiated pioneering research through Myco Alliance LLC on the use of mycelium for bioremediation. It wasn’t until 2016, however, that a significant breakthrough occurred. Together with Ecology Action of Texas, we secured a $50k grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation for the Montopolis Wetland and Creek Rehab Project. This project was centered at the Circle Acres Nature Preserve, once a capped landfill and now a 10-acre expanse of restored wetlands,forest, and grassland nestled within the southeast Austin neighborhood of Montopolis.

The acquisition of this grant and the subsequent construction of The Research Stationmarked a pivotal moment in our journey. It provided the impetus for the development of educational programming focused on waste diversion. What better place to lead such efforts than at an old landfill site?

Between 2016 and 2019, our educational initiatives at Myco Alliance flourished, particularly with the invaluable addition of Hi-Fi Mycology to the burgeoning Austin mycology scene in February of 2017. The collaboration with Cory and Sean was instrumental during those years, which would end up leading to the formation of the Central Texas Mycological Society in 2019. Those days though, on average, I along with volunteers, would pick up anywhere between 300-700 blocks per week from their farm near 183 and Burnett. Each block averages about 5 lbs so we were essentially diverging close to 1 ton of spent spawn per week and close to 50 tons of annual waste diverted from landfills. These blocks would instead end up at Circle Acres, at the mycological research station, and get used multiple times.

At our mycological research station at Circle Acres, the journey of these blocks took on various stages. Upon arrival, they rested in our greenhouse, allowing the mycelium to rejuvenate for subsequent mushroom flushes. This process yielded approximately 40 lbs of mushrooms per week, which I distributed to volunteers and local food spots like Curcuma and Bento Picnic on E. Chavez in Austin. This distribution not only provided sustenance but also served as an educational opportunity for volunteers and students attending our classes.

Once the mushrooms were harvested, the blocks were stripped of their plastic bags. Some blocks were broken up for workshops, while others were placed directly into the ground at the demonstration gardens of the research station. These intact blocks retained their structural integrity, maintaining the fungal lamination crucial for fruitbody development. Consequently, patches of mushrooms consistently dotted our grounds. After approximately two flushes in the ground, these blocks were unearthed and repurposed in restoration projects around the site, particularly in areas prone to erosion due to increased urbanization.

During this time, Austin was experiencing rapid urbanization, leading to a surge in impervious cover and exacerbating issues with stormwater runoff and erosion. This not only affected the stability of the landfill cap but also impacted riparian zones adjacent to the site. The influx of impervious surfaces amplified the volume and velocity of stormwater runoff, resulting in erosion along waterways and compromising the integrity of surrounding ecosystems.

Amidst these challenges, our restoration projects, fueled by the repurposed mycelium blocks, played a crucial role in mitigating erosion and fostering ecological resilience. By strategically placing these blocks in erosion-prone areas and riparian zones, we were able to enhance soil stability, reduce sedimentation in water bodies, and promote the regeneration of native vegetation. This holistic approach to restoration, coupled with community engagement and education initiatives, contributed to the sustainable stewardship of our natural landscapes in the face of urban development pressures.

In the summer of 2019, the Central Texas Mycological Society (CTMS) emerged from he foundation laid by Myco Alliance, marking a significant transition in our journey. Building upon this milestone, we launched the Mushroom Block Giveaway program, which continues to thrive to this day.

Through this program, we collaborate with local mushroom farms to repurpose "spent" mushroom blocks, diverting them from waste streams. These blocks, once destined for disposal, are now valuable resources for cultivating mushrooms and nurturing healthy, fungal-rich soil. The initiative not only addresses waste reduction but also promotes education and community engagement.

In conclusion, the evolution of the block waste diversion program underscores the transformative potential of grassroots initiatives and community-driven solutions. From its inception at Myco Alliance to its integration into the fabric of the Central Texas Mycological Society, this journey highlights the importance of persistence, collaboration, and innovation in creating positive environmental impact. As we reflect on the history of this program, we are reminded of the profound lessons learned and the enduring legacy of our collective efforts towards a more sustainable future.

As stewards of environmental sustainability, we invite you to support our mission by donating, becoming a member, or volunteering your time. Together, we can continue to make a positive impact on our ecosystem and inspire others to embrace sustainable practices.